This story is part of Ravishly's Throwback Thursday "First Woman" series. Read more posts about pioneering ladies here.

Summer’s almost over, and fall is just around the corner. This temporal fact may make you melancholic or giddy. Either way, what's a better way to get in the autumnal spirit than with a bit of Salem Witch Trials remembrance? Crisp air, colorful foliage, pumpkin patches and contemplation of New England’s Puritan devil hysteria always hits the harvest season spot, no?

In that vein, we’re looking at the very first woman—nay the first person—to be executed in the nine month frenzy of finger-pointing hosted by Salem, Massachusetts in 1692. This disreputable distinction goes to one Bridget Bishop, who may be one of the best representations of the witch trials. Her case reveals the way fighting the forces of Satan in the early colonies could actually function to denounce people who strayed from the norm. And the norm could be pretty rigid in these early, relatively isolated religious communities.

Trouble Brewing

The trouble started in February of 1692, when two young girls of a high-standing family began experiencing mysterious fits and maladies. Concern about witches had long simmered among Puritan communities, so when a doctor examined the girls he recognized right away that the amorphous symptoms weren’t simply in the girls’ heads—witchcraft was afoot in the town! The girls reportedly agreed with the diagnosis (the scientific method at its finest), and promptly pointed out the sources of their demonic suffering.

Apparently the cherubic girls and good doctor were on to something, because soon accusations of witchcraft were flying every which way in Salem, ultimately incriminating more than 150 people—the majority of which were middle-aged women. Wouldn’t want to kill the young and pretty ones, after all.

A Witchy Woman in Color

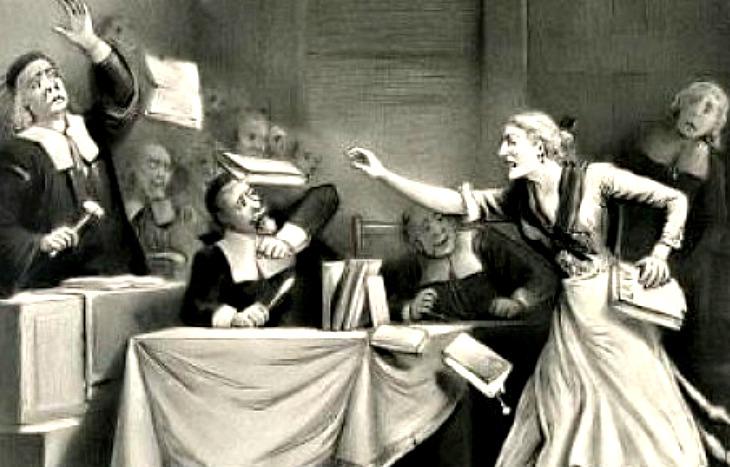

Now that Salem had accrued a solid pool of witchy candidates, a special court convened in June to hand down godly justice. And they knew just who to start with—a woman who had been a thorn in the side to the reputable and dour elders of the village for years, Bridget Bishop.

Bishop had been accused of witchcraft more than any other person in the town. Coincidentally, she had previously racked up a number of enemies through her lascivious lifestyle: She had married three times, she dressed in garish colors, and she frequented town taverns. I mean, does it get any witchier?

Some accounts indicate Bishop single-handedly dominated the town’s gossip with her public spousal fights, late nights of entertaining guests in her home, drinking and playing an apparently forbidden game named “shovel board.”

Historical accounts of Bishop include a range of descriptions, but modern historians agree she “possessed a quick wit and independent spirit.” A witty and independent woman? In Puritan Massachusetts? You know that doesn’t end well.

Certain townspeople reportedly even felt Bishop’s “dubious moral character” was causing “discord [to arise in other families,” leaving the youth “in danger of corruption.” How convenient, then, that a woman clearly disregarding the norms of her religious community became target number one for the witchcraft inquisition. Her choice to wear color seemed especially abhorrent to the court, and her “showy costume” of a red bodice was actually used as evidence against her, since fashionable apparel was largely regarded as a “snare and sign of the devil.”

Desist and Recant

Sure enough, on June 10 crowds gathered to watch Bishop’s public hanging on what was dubbed “Gallows Hill,” despite her continued profession of innocence and her assertion that she had never, in fact, met the devil.

The court went on to execute 19 more people (including one man who was crushed to death) before Massachusetts Governor William Phipps decided to put an end to the witch trials late in 1692. And in what should be a surprise to no one reading this, several of the townspeople who had testified against Bishop recanted their accusations on their deathbeds, asserting they had been “deluted [sic] by the Devil.” The devil again, huh?

Lessons Learned?

It’s understandable that the Puritans were a bit on edge in 17th century America. Repulsed by the lifestyles around them in Britain, and victim to their own persecution on the foggy isle, the community had sailed across an ocean to face an uncertain future in a new, and decidedly wild land.

But their massive overreaction to perceived moral threats, and their eagerness to shed rationality for superstition, has left them as the prototypical example of crazed scape-goating. And as Bridget Bishop reveals, witchcraft could translate more into an excuse to purge those not going along with the societal program, than with any actual threatening behavior.

A fact to remember in the face of the seemingly universal human desire to punish outliers . . .